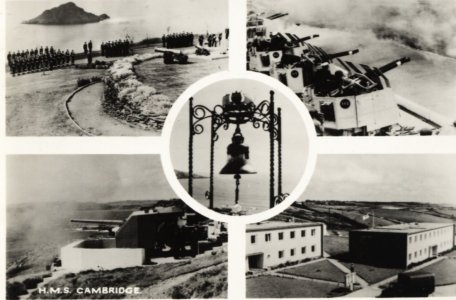

| HMS Cambridge

|

This was my first major contract, and it started in April 1971 (Easter), nearly two years after I joined the company.

So it was an exciting prospect to be deployed on site for

trials of a brand new military system. This was in fact the development version of WSA4, destined for the impending Amazon (Type 21)

class frigates that were under construction at Vosper Thorneycroft's dockyard at Southampton.

By then I had a good knowledge of a range of the company's

processor designs, and some practice in writing test and demonstration software. In those days we designed and built

our own 24-bit computers out of crude logical components; the processor unit (now the size of a fingernail)

would then occupy a whole 19" rack with up to 19 circuit boards and a maximum of 12kBytes intermal RAM. There

were additional memory modules, but these amounted to only a couple of hundred kilobytes. This was serious

stuff. Can you imagine what a 21st century programmer would say to such slim resources?

The installation and trials took place at HMS Cambridge, a land-based naval gunnery school at Wembury Point near Plymouth

The deployment spanned about a year, from Easter 1971 to May 1972. We had our computers set up in rooms behind a balcony

overlooking Heybrook Bay and with an excellent view of the Great Mew Stone. For our own purposes the Eddystone

lighthouse (at a range of 18.8 km and easily within range of the shore battery) was an excellent landmark, but

with our unproven computers controlling the new Vickers 4.5 inch gun, no doubt many lighthouse keepers were glad

that it was fully automated and they didn't have to go near it. Our tracking radar (from Selenia in Italy) was

capable of distinguishing the actual lighthouse from the stump of the original one, right next to it. While this

might not sound very impressive against 21st century systems, it was a serious advance in those days. In fact, like so

much of our work in the development departments at Ferranti, the whole project was very much on the leading edge and

presented many interesting technical challenges.

My initial experience at HMS Cambridge set the scene for the remainder of my time based out of Bracknell.

From here on, my work with Ferranti required me to have one foot in the detailed hardware designs, and the other

in the system and test software. For this reason, and with respect to the RN's fondness for acronyms, I described

my job as dealing with Software/Hardware Interaction Troubles. In addition to this I very often had one hand in the

peripheral equipment (radar, guns, missiles, comms etc), and the other in the design of simulators for system

development. As will be seen later, I sometimes found myself having to become an instant expert in some other

manufacturer's products.

Meticulous attention to detail during the year enabled us to improve our system to the extent that it was capable

of hitting an airborne tow cable at a range of several kilometers with a non-exploding shell. Perhaps not very often, but

it was very impressive when it happened. Fighter planes flying overhead provided us

with towed radar reflector targets, and the lengths of tow rope were designed to allow the planes to pass overhead

before the reflector targets came within range. But on more than one occasion we took out the reflector and several

sections of cable before the pilots surrendered and we had to cease firing!

Despite the enormous number of individual components used in our designs, the Ferranti equipment proved to be

extremely reliable. Nevertheless, because of the importance of our work and the hazards from large, fast-moving equipment

under our control, we were required to run a suite of test programs every day. These tested the main computer and all the

equipment attached to it. My problem was that I got bored sitting around waiting for things to happen all the time, so I

decided it would be fun to write a sequencer, so that all the test programs could be run at the same time. In principle

this was very useful, but nobody else believed it was possible and wouldn't let me do it. That's red rag country! So I did it.

The core I designed was what would now be called a multi-tasking real-time sequencer, and it worked a treat. It has

to be admitted that, as systems became more complex, and the designs (for economic necessity) became more dependent

on pre-prepared common elements, I felt that the challenge of efficient design (especially in software) was scuppered. But at

that time everything was possible if only you were willing to have a crack at it.

One day I had this test program running when the senior site managers turned up for the day's trials. Nobody thought of

asking me what was going on, so I said nothing and let them run around in a panic wondering why all the lights were

flashing and the equipment was dancing about frantically. I had proved my point, and the program was used regularly after

that. But they still wouldn't let me play with the gun.

I should explain that in those days we didn't use operating systems. They are notoriously resource-hungry, and with the

available memory and processing power the

overheads had to be kept to an absolute minimum. Even in the operational systems everything was written in low-level

mnemonic code for speed and efficiency. While some work was done in a higher level language by the mid 1970s, it wasn't until

the company started using commercial microprocessors in the 1980s that the use of operating systems and high-level languages

really took off. Perhaps this was a commercial necessity, but it always seemed to me to be a retrograde step: encouraging

programmers to isolate themselves from the inner workings of their product, and wasting a large proportion of the available

power. Commercial systems had long since gone the operating systems / high-level language route, but they didn't have to be

installed in cramped compartments using only components that could stand 10g forces whenever the ship hit a wave.

There was a little guest house in Heybrook Bay, where we would put up visiting engineers. The old lady who ran it was

a dear soul and much liked, but that didn't stop us from playing an awful trick on her one day.

We had been tracking aircraft in the morning when there was a power cut. In those days, uninterruptable power supplies

(common now) were very bulky and unaffordable, so everything went off and we had to suspend

the trials for some time. Our guests therefore went back rather late for dinner, and appeared with very long faces at

the guest house. The landlady wanted to know what was upsetting us, and we showed great reluctance in talking about it.

In the end we let her persistence win through, and explained that the power went off while an aircaraft was on task

overhead. The pilot didn't stand a chance, and left two small children behind. She was almost in tears to hear this

news and went straight away to tell her daughter. The implausibility of a power cut affecting a plane was explained

in the kitchen, and we all got a big earful! I think our visitors very nearly ended up wearing their dinner.

Even though the IRA was particulary active at that time, and there were strict security measures in place at the

gates, there was a public footpath right along the foreshore. We would nip down there for bathing and to catch the

occasional spider crab. But the best place for catching spider crabs was round the coast at Start Point. That was where

the navy would fly weather balloons for us to practise tracking on our radar. But one day the tether broke and the balloon

went for a tour of dartmoor. With some simple geometry, an OS map and an allowance for the wind and rates of descent,

I managed to calculate its eventual landing point to within about a half mile. The pick-up team had an easy job to find it,

but more of a problem extracting it from a herd of very curious cows.

Overall, Plymouth was an excellent place to be on site. The naval dockyard was busy and provided employment for a

range of local services and industries. And with shops, restaurants and cinemas, the town centre had all the things

you could reasonably want. I need hardly say that the night life was excellent, with many clubs to suit various tastes and tastelessness. Couple

this with easy access to coastal walks and dartmoor country pubs among other things, and it was pretty much a dream

location for a young engineer on expenses. I remember there were four small restaurants in the main shopping centre:

English, Italian, French and Greek. I visited each one and discovered that they were all owned by the same Greek person,

and had almost exactly the same menus.

For me this deployment was a big learning curve, as I was able to see for the first time how this new technology made things

happen in a complex and sometimes dangerous environment. Not many people get to experience the whole picture, from the

details of component and low-level software design, through prototype production and design proving, to shooting things out of the sky. So, while the

daily routine had its tribulations and frustrating restrictions, in retrospect it formed a very sound base for the

path that my career would afterwards take. There is always the suspicion that when you are away from base your career is effectively on hold because you are out

of sight, but I wouldn't have traded the variety and technical interest for anything else.

It was in Plymouth that I learned my first Italian. We had an Italian engineer deployed with us to look after the Selenia

radar equipment, and he enjoyed a good night out. We decided that it would be useful for us to be able to share notes

in Italian, partly because we could say things that others wouldn't want to hear, and partly because English girls went mad

for a convincing Italian accent. It sort of worked, but I don't remember learning anything that I would care to repeat,

even in English.

While I was away, two things happened. I grew a beard, and the company expanded into a new building in Doncastle Road, some

distance from the main site on Western Road in Bracknell. The beard was fun: on many occasions I would be walking along a

passage and see someone obviously unsure whether they recognised me or not. But the move to Doncastle Road gave the department

a great deal more space, and we were able to handle a greater variety of contracts as the company steadily expanded.

After finishing at HMS Cambridge I spent a while at Bracknell doing works development and design proving of other systems

intended for HMS Amazon, and became something of an expert on the preparation of trials documents.

|

| HMS Amazon

|

Before starting on this period I should explain a few things about the development of a new ship for the RN. After

all the contracts have been sorted out with the shipbuilder (in this case Vosper Thorneycroft of Southampton) and

principal subcontractors (in this case Ferranti, Sperry, Shorts, Marconi, Selenia, Rolls Royce and others), detailed

design and construction begins. When a new class of ship is introduced (in this case the Type 21 frigate, otherwise known as Amazon

class after the first ship in the class) the MoD wants leading edge technology so it can remain serviceable for

a useful length of time, perhaps in the region of 20 years with a few upgrades along the way. Therefore, the shipbuilder and the principal subcontractors usually have a lot of work

do to to prepare their new designs, thoroughly test them, and get them into manufacture. So while the shipbuilder

is working on the hull, the subcontractors are under pressure to get a lot of design and development work done.

One of the games played by shipbuilders was called "last across". The idea was that if the hull is running late,

they say nothing in the hope that one of the subcontractors is also found to be late with their bits and pieces.

The shipbuilder then rearranges the programme to show that the subcontractor is holding everything up; this buys

time for the shipbuilder, and lands the subcontractor with potentially massive liquidated damages (cash

penalties for lateness). Subcontractors obviously play similar games, keeping quiet for as long as possible if their programme

runs late, in the hope that somebody else will own up first and get them off the hook. This game could also

be played using the "force majeure" rules. Force majeure is a situation when

something outside the control of the company delays the programme; it might for example be a change in requirement

from the MoD, extended foul weather or terrorist activity.

In this case it was a stike by the union. In those days trades unions were very active and very destructive

(strikes became known in other European countries as the British Disease). The company had been turning a blind eye to

the showing of "blue" films in the empty engine compartments before the Rolls Royce Olympus and Tyne engines were fitted.

But when the company needed an excuse to claim force majeure to buy some catch-up time, they fired some of the

people organising the films. The union immediately went on strike for weeks, demanding reinstatement, and while

that was being sorted out the company was getting on with other work. It came as an eye-opener for me that the

trades unions could be manipulated in this way, and after that I treated everything published in the newspapers with

great scepticism. Even now, all sides (and a variety of interested spectators) in an industrial conflict will tell

you what they want you to believe, embellishing it where they can with emotive hyperbole. The only thing you ever really

know is that you are not being told the truth.

So, while I was down at HMS Cambridge, HMS Amazon was being built. When I returned to Bracknell, between 1972 and

1974 I was working on the equipment to be fitted to the ship, and this was delivered and installed by a skeleton site

team. At the same time I was preparing technical maintenance information and trials schedules. I then joined the

ship in March 1974 and lived locally in Southampton and Portsmouth until April 1975 on the completion of sea trials.

The ship was commissioned on 11th May 1974 and Princess Anne, the Princess Royal, officiated. I wasn't invited to that party,

but our site manager (an ex Chief Petty Officer) made sure to explain to HRH that her mother was getting excellent

value from Ferranti. The comment, thankfully, was taken in good humour. The ship was then sailed to the naval dockyard

at Portsmouth, and the site team rejoined her there.

It should be explained here that when a ship is commissioned she becomes the property of the navy. This doesn't mean

that it is finished, only that the hull is watertight, the engines, radars and essential communications equipment

work, and that people can live and work on board in reasonable comfort. In particular, for a first-of-class vessel there are

bound to be a number of things that turn out to work better on paper than they do at sea. So there is still a lot to be done,

including an extensive programme of harbour

and sea trials. Harbour trials (HATs) are a variety of tests that can be done while in port, and for reasons of economy and

convenience, as much as possible is done in this way. But there are important tests that have to be done at sea (SATs).

Throughout this time the ship is under the direction of the RN appointed captain (customarily a Commander on a frigate), and

the subcontractors work in collaboration with the ship's crew.

From our viewpoint the change to navy control was a real blessing. No more the jackhammers, welders and building-site

hazards. No more the infinite array of obstructions such as access to the ship and electrical power shutdowns. Now the ship is tidied up,

everything is properly stowed, onboard power systems are running most of the time and we have access to the ship's own technicians to

help us when we needed to be in several places at the same time. We could now really get on with our job uninterrupted.

The only little problem was the game of "hunt the ship" played at frequent intervals. For some reason the dockyard was

constantly reassigning berths as various ships came and went. Amazon would be moved from one place to another, and would

sometimes be berthed outboard of another ship, so you had to climb over one or two other ships to find your own.

My own particular problem was that I suffered from vertigo. Ordinarily at sea level this shouldn't be much of a problem,

but I frequently had to navigate across and between dry docks. These things are vast and very, very deep! So

crossing the narrow caissons (pronounced locally as "cassoons") and narrow temporary walkways was very often a seriously knee-trembling experience. More

about my vertigo later, and what else I did that made no improvement to it.

It was soon after handover that the captain decided to try out the engines and see whether the ship would get somewhere near

it's advertised top speed. I was enjoying a g&t in the wardroom at the time, and heard the warning to make sure everything was secure.

So I held on, and just as well I did. After a few seconds of heavy vibration, the curtains in the compartment were hanging at 45 degrees

as the ship took off. And as the hull approached the design speed the vibration coming through the structure was incredible. Until then

I thought that military specifications on shock tolerance was all to do with exploding shells; I had no idea that the worst

conditions for on-board equipment were self-imposed. Anyway it didn't last long before the captain announced that we were going to stop.

This ship was fitted with variable-pitch propellers, which meant that you could leave the engines going at full blast, and simply

change the direction of thrust. The effect was to stop from 30 knots to nothing in less than the length of the ship. Just as well I had

finished my g&t by then!

On one occasion we were berthed outboard of a destroyer (I think it was the new HMS Sheffield), and there was an awful stink on

her flight deck. On enquiry I found that the ship's company had been given a week's leave and had just rejoined her. In their

absence the "yompers" (bacteria that consume the human effluent in the septic tanks on board) had mostly starved, and the

survivors were having difficulty coping with the sudden demand. By the following day the smell had largely gone, partly

as a result of feeding the yompers with dried milk, in large quantities. I am still waiting to see the instructions on

packets of dried milk in the shops: "suitable for babies and septic tanks, but not necessarily at the same time".

The harbour trials were managed successfully and we all got on very well with the ship's company. But in August 1974 we weren't quite ready

for the sea trials when we received news that the ship was ordered to sail to the West Indies for warm water trials. It was

important that ships could operate anywhere in the world, and warm water trials were intended to make sure that everything

worked in the heat. Including the crew. Our site manager had to decide whether to suspend operations until the ship returned

in a couple of weeks, or take advantage of the situation. As a very experienced sailor his decision was easy and immediate,

and his civilian team would just have to make the best of it.

I couldn't join the ship outbound as I had to reshedule my SATs document preparation to cope with the new opportunities, and needed to be in UK,

but I flew out to join the ship in Trinidad when she arrived a few days later.

I had been given a locked satchel to contain my trials documents, which were classified material and not to be shown to anybody

(including customs). At Heathrow I explained the situation to security and showed then a letter of authorisation from our

security chief, and they immediately thrust me to the front of the checkin queue. I almost felt guilty, but I controlled it.

The problem occurred at Trinidad airport. The customs officer insisted on seeing the contents of my secure bag, and refused

to accept the letter explaining that it was UK classified information destined for the ship. After a very long "yes-you-will,

no-I-won't" interlude I asked for the airport security chief, and he wandered over shortly afterwards. I was then able to negotiate

a solution: the satchel would be put in the airport safe until I could return with the ship's caption to reclaim it. I was

then able to join the ship.

By then it was early evening and the ship was preparing to receive local dignitaries and expat Brits, as was the custom on arriving

at overseas ports. Even though it was then midnight by my body clock I was required to join in the preparations and meet

a selection of very attractive young ladies at the on-board party. The things I did for the company! After that we decided

to go ashore for a drink or two, and ended up in an excellent nightclub called the Miramar. Other than the quality of

the entertainment, the other remarkable thing was that it was next to the vegetable market. The street was littered with vegetable

waste and I distinctly saw a creature rather like a frog, but the size of a domestic cat! It was come and gone in a blink, but

the thought of such strange creatures bounding around the dark streets made me wish I was wearing cycle clips.

So it was well into the following day by my clock before I hit my bunk. Looking and feeling

not quite my fluffiest I had to make an early start to get an officer to accompany me to the airport to reclaim my secure bag.

This was an early lesson in time management. Throughout my life visiting ships I found the quickest way for a civilian to be

accepted among a ship's company is to show the ability to survive a very late night, and still be fully abluted and hungry for a full breakfast

by 0730. On this occasion there were no porridge or runny eggs - they were reserved for when the ship was at sea.

The captain was not an option as my escort, but the Weapons Electrical Officer was a large and athletic man with a posh voice and an impressive

array of stripes. He would do nicely. On arrival at the airport I found the security chief, and he was very helpful

in locating my bag. The problem was that the previous night's security supervisor had lost the key to the safe!

They searched the airport, but nobody could find it; and the

person concerned was fast asleep and not answering the telephone. We had to wait for ages, but in the end someone found a

way of opening the safe, and the bag was delivered, unopened.

The other thing of note on that little outing was the sight of

the Chinese laundryman sitting on the bow of the ship with a short stick and length of string to make a crude fishing tackle.

With the sort of pollution found

in dockyards I fear to think what sort of poisons his dinner would have in it.

I knew he was on board, but he confined himself to his steamy compartment and didn't ever seem to mix with the ship's company.

He was no doubt saving every possible penny to send home to his family. His nationality was confirmed on a later

date when I found my mess number neatly stiched inside the collars of my shirts. In Chinese.

While we were there the captain decided to conduct NBCD exercises. This involved pretending that the ship was under attack

and simulating various forms of damage. That would involve a lot of running about and complete disruption to our own

work. This would not be a good place for civilians, so we elected to spend the day ashore suffering in

silence in one of the hotels' swimming pool bars. It was in such a position that we received news from the ship that Ferranti

was bankrupt. No joke - this was for real!

The company as a whole was in financial difficulties, mainly due to some of the original

subsidiaries having become very expensive passengers. In particular I remember that Transformer Division, which

was a major part of the original company, had been failing to get major contracts for a while, but the then owner

(Sebastian de Ferranti, grandson of the founder) wouldn't let it go. As a result everybody feared for their jobs. So we

refilled our glasses and wondered what to do next. Then another message came from the ship's Supply Officer to say that as

individuals we were no longer creditworthy, and our mess accounts would have to be settled immediately. And no more foreign

currency transactions. This was getting serious, but we were stranded ashore for the time being and unable to do

anything. So we had another drink while we thought about it.

That evening, when we returned to the ship, all was quickly resolved with the Supply Officer and we received some

helpful messages from our department management. It turned out that the news was largely invented by the press, and

that in reality the company had been bailed out by the government in return for appointing a "proper" Managing Director.

The owner, Sebastian, was a second-generation rich kid. He illustrated the common "rags-to-rags in three generations"

pattern, seen in many other places: grandfather comes to England to set up a business; his son inherits the business and

a lot of the entrepreneurial spirit required to continue developing the company; the third generation inherits a lot of money and

a desire to do nothing more than spend it. Then the company falls apart because nobody has been appointed to run it properly.

Some months later the new encumbent was agreed and appointed, and broke up the company into separately accountable trading units.

Overall governance was maintained at group level, but the individual companies were largely autonomous and unencumbered

by each others' failures. This meant that the irrecoverable "passengers" were ditched, and the rest of

us carried on under our new names. From that time, Ferranti Ltd., Digital Systems Division became Ferranti Computer Systems

Limited. This may not have a lot to do with HMS Amazon, but it's all part of the rich pattern that made up my life at the time.

Before leaving the West Indies the ship organised a banyan. This is a sort of beach party, where we anchored off a quiet

stretch of beach belonging to Bequia, a little island in the Grenadines. The ship's boat was used to ferry all sorts of equipment,

food and drink, and we occupied the beach for most of the day. The sailors tried to climb the coconut palms, but

failed, so we offered some local children bottles of tonic water and they shinned up the trees to get us a quantity of

fresh coconuts. That is where I discovered the pleasures of pouring white rum into a coconut, and then topping

it up as you drink from it. It ends up as almost neat rum. And the coconut tastes pretty good afterwards.

Thus, we completed our deployment in the West Indies, bought our souvenirs and sailed back to the UK.

This time I stayed with the ship for an uneventful return journey across "the pond". On the way back the ship's

company played a variety of games on the flight deck. It wasn't a big flight deck -

just about enough for a little Lynx helicopter to land safely. I got roped in to a game of Uckers (a game

for which to the best of my knowledge nobody actually knows the rules) and deck hockey, and somehow survived being bounced off

the guard rails a few times without going overboard.

It was later that summer, as we were quietly carrying out trials somewhere off the coast near Plymouth, when the ship received

a message that there was a mine in the middle of the channel! Apparently one of those big, spiky things used for minehunting

exercises had slipped it's mooring on the seabed and popped up to the surface. A passing yachtsman was seriously unimpressed

and complained (from a safe distance) to the coastguard. The gunnery officer on board was an explosives expert, so we were

despatched to sort it out. Once at the location, it was the work of minutes to send out a rubber dinghy and

destroy the offending aricle (a non-explosive dummy).

By then our trials schedule for the day was in tatters, so we aborted trials, and the captain decided we could all have a swim.

We were then almost exactly half way between Plymouth and Cherbourg, and the sea thermometer registered something tolerably

warm due to the gulf stream. While at sea, food waste (all rubbish is known as "gash") used to be dumped overboard ("ditched")

for the fish. I don't know whether they still do that, but it is inclined to attract sharks in those waters.

So there was a pipe (an announcement over the loudspeaker system): "Hands to bathe in thirty minutes. No ditch to be gashed". This

was followed a few seconds later by another pipe: "Belay that last pipe - no gash to be ditched". I thought the expression "belay",

which means to tie down or secure, was rather poetically applied to an announcement, as if we were all to run around catching bits of it in the air.

As it happened, it was a rather pleasant swim if hard work climbing up the ladder onto the deck afterwards.

During peacetime, the RN performs a variety of social duties, generally known as "flag-waving". They were partly to cheer up

the expat communities, partly to host parties for the resident dignitaries, and partly to show off our wonderful

technology. Whatever the reason, in October 1974 one of the destroyers (I think it was HMS Bristol) was designated

to be sent on a tour of Northern Europe. Unfortunately, a couple of days before departure she had a fire in the

engine room that did substantial damage, and she couldn't sail. It was decided to send Amazon in her place,

and I remember receiving a telephone call from the captain one evening, asking whether the Ferranti team

wanted to come with the ship, and if so to be on board and packed for a week by 0730 the following morning. I agreed

on the spot, because we needed sea time for our SATs and I knew exactly what our site manager would say. Then I

tracked him down and he confirmed it formally.

One of the many differences between a frigate and a destroyer is the size of the ship's complement. For example, in the

wardroom on Amazon there were only thirteen officers, a lot less than on a destroyer. If I remember correctly they

have something like twenty five. So the civilian team were invited to join

in on the various official visits to make up numbers. We visited Amsterdam and Bremen. Amsterdam is well known for its

interesting night-life, and it did not disappoint on that occasion. But my favourite memory started as what seemed

a very dull duty.

We were asked to make up numbers on a coach trip to The Hague for an official visit to the consulate there. I went along

in my best bib and tucker expecting

a dull reception, but it turned out to be quite interesting after all. Lots of pretty girls to talk to, and an

inexhaustable supply of champagne. I had no idea how much I had been drinking, as there were velvet-jacketed stewards refilling my

glass every time I took a sip. I don't remember the name of our host, but he certainly knew how to throw a party.

Our coach was shared by the officers from another frigate visiting Amsterdam at the same time, and on our merry

way back to the ship we were challenged to continue festivities in their wardroom. We politely complied, and drank them out of gin

so the party had to be continued on Amazon. In the end it got very late, and we were all quite "relaxed" when we finally turned in.

Bremen was an interesting old town, and thanks to the hospitality of our German municipal hosts we had a really interesting

couple of days. Being a civilian, I enjoyed the privileges of socialising with the officers one minute, and the

ratings (especially the CPOs) the next. So it was that one of the places I visited was Kaffee Hag, where they made a wide range of beverages. We saw the massive

coffee roasting ovens, and their impressive electronic control systems. But the most entertaining part of our visit was when we

were taken to the end of the production line, where the packs of coffee were loaded manually into boxes.

As we watched the ladies handling the packets with practised ease, one of the ratings decided to help. The result was

pandemonium. He quickly got behind, and because his behaviour was causing the other ladies to laugh, they were all

losing the plot. There were packs of coffee falling about everywhere. As if this wasn't bad enough, I then caught sight

of another sailor riding the rollers in amongst the coffee, trying to retrieve his hat that someone had thrown into the works.

I think it would be a long time before another crew would be invited, but nevertheless we were each given a pack of goodies to take away.

The Bremen Ratskeller was a more formal occasion. It was famous, as with Ratskellers everywhere, for the quality and

quantity of wine in the cellars. The officers (me included, again) were invited to a wine tasting, and had a really interesting talk to illustrate the

various quality wines. I think we were supposed to spit out the wine so we wouldn't get drunk, but most of us forgot. There's no doubt

we were greatly impressed with the hospitality we received from the people of the town.

I could mention here that officers and senior ratings in the RN have a very special talent. After a busy "run" ashore, when

they are rather "relaxed", and having some difficulty standing up, their demeanour changes completely when they reach the brow (aka gangplank) of a

ship. All of a sudden they are ramrod-straight and steady as a rock as they climb up to the deck. And they

somehow maintain this composure until they are out of sight below decks. Junior ratings generally have no such

skill, and end up on a charge for disorderly conduct.

The next overseas visit was on cold water trials, in February 1975. This followed a similar pattern to warm water trials except it took us into northern

European waters, through the Kattegat and into the Baltic Sea. This was during the "cold war", and here we were right on

Brezhnev's doorstep. No doubt we were watched with great attention by numerous surveillance installations, but we were only

"buzzed" once by a MIG fighter. We had turned off all the radars so as not to give away what they did, but I have no doubt

their patterns had already been intensively studied. I think the MIG was sent simply as a sort of courtesy, to show that

the Russians were interested and watching us. Maybe they wanted to bait us into turning on some kit that we didn't want them

to know about.

The most memorable part of our trip was a couple of days spent at Malmo. Some of us rented a coach to take us past the massive ski jump

that had been built for the 1952 olympics. We spent the day skiing and I ended up with very bruised elbows! But the enduring memory

was the way everybody was smartly dressed. Perhaps there was a lot more money for people to spend in Sweden, but they

certainly made the British look an exceptionally scruffy lot on the streets. Mind you, when I look around me now, I don't

think much has changed.

* * * * *

I visited Amazon again in late December 1976 when she was at Gibraltar. I've forgottten why I went, but it was only for a couple of days.

During my visit the wardroom was invited to an informal reception at the resident army barracks. Someone organised a landrover, and

about eight of us piled in, with myself and the captain on the open tailgate. It made for an interesting ride over the lumps and bumps

of the winding, narrow roads leading up the hill.

When we arrived we were greeted by the sight of a couple

of impressive statues at the bottom of the steps in front of the main entrance. We piled out of the vehicle, and as we approached

these "statues" they suddenly burst into life and came smartly to attention. Not for an erk like me of course, but for the captain who was leading our group like

a mother duck at the head of an untidy chevron of companions. The "statues" must have been most impressed to be told to expect the wardroom

of one of Her Majesty's newest warships, and then to be greeted by a group of men piling untidily out of a beaten-up landrover, nursing bruises.

But the buffet was half decent, and there was plenty to drink, so we felt no pain on the return journey. I remember there was masses of food

left over, but I expect the squaddies polished that lot off in double-quick time as soon as we had gone.

The return flight was interesting. I had bought a quantity of cigarettes and alcohol at duty-free prices, and came through

the red channel at Heathrow. I explained what I had got, and the customs officer wanted to check it. So he searched my bags, and

couldn't find any of it! So I paid no tax, thinking perhaps I had left it on board after all. Meanwhile, in the green channel

someone came past with bags clinking like a brewer's van. I saw them politely stopped, and quantities of spirits were

produced and lined up in rows. Did they think that customs wouldn't be paying attention on Christmas Eve?

When I got home, I found all my duty free items in my bags. How they hadn't been found by customs remains a mystery to this day.

That was the first and only time I flew Dan Air, which was also a memorable experience: the seats were flimsy, and the child behind

me was trying to give me a permanent injury. I am prepared to believe it had outside toilets, but it was a mercifully short flight so I didn't check.

|

| ARA Veinticinco de Majo

|

Throughout my time at Ferranti, working on naval systems, I was almost exclusively involved in RN work. Others worked on ships for

foreign navies. But as you can tell from the name this Argentine aircraft carrier was the exception.

She was originally built as an aircraft carrier for the RN in 1944, with the name of HMS Venerable, and was sold on to the Royal Dutch

Navy as HNLMS Karel Doorman after only a few exciting wartime years in 1948. I can't help smiling if I think of her being

advertised for sale by the MoD: "Aircraft carrier. One careful lady owner.

Full service history. Buyer provides own aircraft and crew. Best offer over �10M. No time-wasters please".

While she was in the RDN she was refitted with new radars and various other equipment before being sold on to the Argentine

navy about 20 years later. This vessel had a displacement of about 20000 tons and was used to carry some helicopters

and light fighter aircraft.

I visited the ship at her base in Bahia Blanca on two occasions. Once from July to August in 1976, and again from April to June in 1977.

A total of about 18 weeks. On each occasion I went with a small team comprising a radar signal specialist, a site manager and

a programmer. The ship had been fitted with Ferranti computers and we were sent to check out our equipment and trial it

for acceptance by the Agentine Navy. Although I had spent a short time on HMS Hermes, this was the first time I had

worked on an aircraft carrier doing what aircraft carriers were supposed to do. During my visits there were many interesting events, some

related to the nature of the ship and its equipment, and some arising from the very different naval culture that they have.

I will not attempt to present a chronological account because I have long since forgotten what happened on which visit. So I shall

simply split the account into two parts: mainly ashore, and mainly aboard ship.

Ashore

On both occasions the visits were arranged at short notice. The first time, I was provided with a Linguaphone language

course in Spanish. But with everything else going on I had no time to use it. So I arrived at Buenos Aires airport with a very

limited knowledge of the language. All across the atlantic I had been staring at a sign on the seat in front, saying "Your lifejacket

is under your seat"; and on the next seat it said "Su salvavida esta debajo su assiento". But on arrival in Argentina I found that this knowledge of

the language was rather limited in dealing with my immediate purchasing needs.

In those days I used to smoke, and I had run out of lighter flints; I had one of the earliest pocket calculators, which needed

frequent access to mains power and required a plug adaptor; and I needed a map so I could drive to Bahia Blanca, a distance of about 700 miles by road. From the

hotel I walked to the main shopping precinct and looked for a map in a kiosk, which attracted the attention of the stallholder. It

turned out he spoke perfect English, so I explained what I needed. To my amazement he shoo'd away his other browsers and shut the stall.

He then took me on a conducted tour of the shops and helped my find everything I needed. I'd been to many places around

the world, and met many people, but never had I found someone so helpful to a complete stranger.

Over the period that I spend in Argentina, I found that this sort of kindness was far from unusual. Most people spoke very good English,

a point reinforced one day when the radar engineer and I were discussing where we could get some sticky tape. A window cleaner working

a few feet from us stopped what he was doing, wiped his hand and came over. He introduced himself and explained that he had never met

an English person before. He had learned English in school, and never knew for himself what we sounded like. His English was extremely good,

with no trace of a USA accent, which I would have expected. We talked for a while, he gave us some directions, and we went on our way very

impressed. Not just with man-in-the-street's knowledge of our language, but with the enormous regard with which they held the

British people.

Most of Argentina is very flat, at least until you go across to the Andes in the West. But not far from Bahia Blanca was a small range of

hills called the "Sierra La Ventana", or "window hills". They are so called because there is an aperture in the natural rock formation, about

two metres high, near the highest point. When the sun is in the right direction you can see it in the shadow cast by the hills. We had been advised that

it was a pleasant walk to the top, a couple of hours on foot from the nearest road. One of the girls we met locally acted as a guide, and

we decided to have a look. The pictures show the view of the road through the window, and the window seen as a tiny spot near the horizon from the road.

It wasn't a difficult walk, although it was very rocky in places; but then it wasn't just a couple of hours either. It seems that Welsh miles had been exported to Patagonia and

spread from there. The view from the top was brilliant, and on the way up I saw for the first time an atmospheric inversion layer. This is where

the land is so flat that, without wind, warm air can remain trapped under cooler air. The visible result is a very thin layer of mist, so thin

that you can only see it edgewise-on, which means you have to be quite high up. This inversion layer went on for miles, with the occasional

break where it overlay a dark ploughed field, which would have been warmer and caused convection overhead.

One evening we decided to go to the cinema. One of the main cinemas was showing "The Romantic Englishwoman", so we thought we

would have a chance of understanding it. There were seven in our group, and I was deputed to get the tickets. Cinema seats were reserved and bookable

in advance, just like in a theatre. So I went to the the cinema kiosk and in my best Castillian (in Argentina they speak a dialect of Spanish, although

"proper" Spanish is always understood) I asked for "tickets for seven this evening". I was presented with a single ticket, which I thought

was odd, particularly as it was so cheap, so I tried to query it: "Is this for seven?". By then there was a small queue behind me and the people were expressing concern in their

mumblings to each other. Actually, far from being irritated by my ignorance, they were concerned for me. Then there was a barrage

of argument all around me. The kiosk attendant was overwhelmed and visibly retreated under the onslaught. It turned out that the performance

was timed for seven o'clock, and he had misunderstood my request. The problem was quickly remedied, and everybody was greatly amused

by the obvious cause of the misunderstanding.

I didn't like to complain when on closer examination I found that all the seats were even-numbered. It seemed that I had been

given alternate seats, so we wouldn't be sitting next to each other. But I needn't have worried because in that cinema all the seats

left of the central aisle were odd-numbered, and all the seats to the right were even-numbered. So all was right, after all.

During the performance we atttracted some attention because we burst into laughter at unexpected times. The Spanish subtitles failed

to convey some of the subtle humour, and we had to spend some time after the performance explaining it.

At that time Argentina had some serious problems. The economy was in free-fall, running at over 200% per month inflation. And there were

people wanting to take a pot at the President. We were not affected by the economy, simply taking the precaution of leaving

our money in USD traveller's cheques until the last minute. The currency had been devalued by a factor of 100, so one "new" peso

was worth a hundred "old" pesos. One day, when I bought a box of matches I was given change with a one "old" peso note. It was worth

about 1/40 pence. Interestingly it had been extensively repaired with sellotape. For that brief period I was a peso millionnaire!

The security was more of a problem. Various roads leading to the town were set up with mobile road blocks supported by platoons of armed soldiers.

So we were stopped several times at gunpoint. The first time this happened, we came over a rise in the road to find an army truck in front of

us with a machine gun aimed straight at us! As we approached soldiers appeared out of the ditches and we were quickly surrounded. The

officer approached me and demanded papers. I produced my passport, and the attitude immediately changed. The officer apologised in perfect

English for the inconvenience and asked politely if he could search the car for weapons. He also instructed his men to shoulder their guns.

The whole incident was conducted with politeness and good humour, although it gave us a bit of a fright to start with.

A few days later I was changing for dinner in the hotel, when there was a knock at the door. When I opened the door I was faced by

a small group of people in leather jackets, all pointing pistols at me! The manager, in an obvious state of excruciating embarrassment

quickly explained that there was a terrorist fugitive believed to be hiding in the hotel, and the security police were instructed to

search the whole building. I invited one of them into the room, and he made a cursory check before thanking me politely and leaving.

On board

At the time of my visits, the Argentine navy was more for show than blow. Since they had fought for their independence from Spain (an

event celebrated every year on the 25th May, after which the aircraft carrier was named) they had no real enemies at sea and had

adopted a fairly casual formality in naval affairs. I felt that their only enemy was their neighbour, Chile, with which they

were in dispute over territorial rights in the antarctic. But the seas around Tierra del Fuego were too hostile for ships to play

sabre-rattling games, so the animosity was vented mainly by telephone and at political conferences.

The only other "enemy" was

Britain, in dispute over governance of the Falkland Islands/Malvinas. It was well known that the Falklands/Malvinas situation, while

being a genuine political irritant, was inflamed in an attempt by the political rulers to divert attention from their economic woes. At the

time I was there, even senior military officers did not take the situation seriously, as I shall later explain.

In earlier work on RN ships I had found that faults in shipborne equipment often led to the computer systems reporting errors in

data. One such situation occurred with the main surveillance radar. When you are far enough from the ship to see it all without

turning your head, you are a long way off, and you don't get the scale of things. The same applies to a photograph. But

when you get up close, you realise that the main antenna, at the very top of the ship, is large enough, if laid flat, to park at least

half a dozen full sized coaches.

This means that it has a lot of "windage" and unless the mechanism is in perfect condition it's motion can become irregular. Such was the case

when the computer showed strange errors in the position of various landmarks. The computer was accused of being at fault, and I had to

explain that the fault was because the antenna was sometimes going backwards. I was not believed - the motors are extremely

powerful, and this just couldn't happen. So I had to prove it, and the radar chief took me to the antenna to have a close look. Bear in mind

I suffered from vertigo! We had to climb a series of ladders, each barely wide enough to fit both shoes side-by-side, right up

the outside of the "island". The platform at the top was a narrow ring around the antenna mounting and gearbox, with a thin

guardrail. It would be very easy to slip under it or fall over it.

The engineer took off the gearbox covers, and it was immediately apparent that the main gear was badly worn. This would easily account for the

erratic behaviour, and he agreed to get it taken out and remade in the ship's workshops. He then disappeared down the ladder,

leaving me holding onto the guardrail with white knuckles.

At the same time, the ship was practising landing aircraft, and a series of fighter jets were playing "touch and go" on the flight deck. Somehow

I forgot my vertigo and, having brought my camera (if I had done that in the UK I would have been put up against a wall and shot), I

took pictures of them. I was so high up it was like being in the gallery of a toyshop. These seemingly toy aircraft were whizzing

back and forth, and the safety helicopters were buzzing around the ship. It almost seemed that I could control them like

marionnettes on strings. But when I got to number 38 on a 36 exposure film I suspected a problem. It turned out later that the camera

had broken the film sprockets and was not winding on at all. So I came away after what must have been a truly unique

experience with no pictures at all!

This was not the only time I had to show the cause of a problem in another piece of equipment. On a separate occasion the

computer was reporting incorrect log data. The log is a device fitted to the bottom of the hull to measure water speed. It is

connected through several other devices, eventually to the computer, and I had to trace the signals back through each of these

to the source. Fortunately claustrophobia is not one of my vices, so I

was able to descend through a number of cavernous and unlit compartments, through hatches barely wide enough for my shoulders,

to reach the offending kit, a long way below the waterline. I would never have believed, when I joined the company to work

in seemingly quiet and comfortable offices, that I would be scrambling about at such heights and depths a few years later.

Each year the Argentine navy organises a Navigacion. This is when, for a few days, the entire navy puts to sea and does some exercises.

Bear in mind that, unlike the RN which is constantly fighting a war somewhere, their navy has very little to do. So they

have to find an excuse to go to sea once a year.

Before we went to sea it was planned to land and take-off aircraft, so they had to get the steam catapult working

before they left. The steam catapult consists of a big pipe running along under the deck, with a slot along its length.

Inside the pipe there is a plug, and this is attached to the nose of the aircraft, through the slot with a loop of leather. When a valve

is opened steam under great pressure is drawn from the boilers and forces the plug to drag the aircraft. The leather strap

unhooks or breaks to loose the aircraft at the end.

This pipe needs to be lubricated with thick grease. One day I was walking across the flight deck and stepped over the slot of

the steam catapult. I caught sight of movement, and immediately suspected rats. But then I saw a glint from white teeth, and

a big smile from a small boy. He was wearing nothing but shorts, and was pulling a big tub of grease along the pipe to

lubricate it by hand. He gave me a cheerful wave and we both carried on. In the UK we might think that this sort of thing is child exploitation,

but that small boy was immensely proud to be in the service of his country, doing a job that no adult could do.

Inevitably, a number of ships were unable to join in because necessary equipment

such as engines were not working properly, but the Veinticinco de Majo was leading the fleet. We had been given warning,

so we were on board with our overnight things and looking forward to the trip. We also needed the sea time for our trials.

We had been at sea for two days, and we were working in the computer room with the lieutenant computer officer when there

was a signal calling for the officer of the watch. This was one and the same person, so he begged his leave and left us. He

was gone for a long time, and we asked him on his return what was the problem. He was clearly feeling uncomfortable, so we

persisted (as you do). It turned out

that two of the crew had been found in the same bunk, and had been arrested for indecent conduct. The officer of the watch was

required to authorise the arrest and see that they were put in the brig (the on-board gaol). So we asked whether

they were locked in the same cell. The effect was dramatic. The officer's face went completely white, and he ran from the

compartment. He reappeared a few minutes later looking much more comfortable.

While we were at sea the aircraft had another game of touch-and-go. At the start they weren't allowed to land because the steam catapult

couldn't be relied upon to get them off again. But later on a few of them landed, presumably to be craned off when the ship returned to port.

On this occasion I was able to be with the deck controller on the port side. The position was over the edge of the main flight deck,

so if it all went wrong the aircraft would (hopefully) slide over his head into the sea without taking him with it.

The experience was unforgettable. Fighter aircraft aren't as stable as other small aeroplanes, and have to take off and

land at much higher speeds. Also, they need the assistance of steel "arrestor" wires connected to massive hydraulic dampers below decks to

help them stop before they run out of ship. But, in case they miss the wires with their hooks, the pilots are trained to give it the beans as soon as they hit the deck,

so they can get safely back into the air. Normally, aircraft "flare" just before touching the ground, which is to say that

they reduce the rate of descent to soften the impact. But aircraft adapted for use at sea are required to

fly straight into the deck at an angle of about 10 degrees. So, from a position almost directly underneath the wing at the point

of impact (the wingtips were no more than a couple of metres away), the

closeness, the speed, the impacts on the deck, the vibration and the deafening noise are truly extraordinary!

In all this sound and fury the deck operator is saying

"up a bit" or "down a bit" into his radio to practise managing without the automatic deck approach lights. The excercise also helped me to understand

the problem of getting any rest if your cabin is under the flight deck: although the deck is solid steel and several feet thick, if you

think you have problems with the person in the the upstairs room dropping shoes on the floor at night, imagine how it would feel

if they started landing aircraft! Since you don't have the benefit of seeing the aircraft approach, it must be an alarming experience,

which I was thankfully spared.

In the wardroom of an aircraft carrier there are a great number of officers, and the most senior (known as the First Lieutenant,

or more familiarly, Number One) might carry the rank of Commander on such a ship. He is the most senior officer to be

found in the wardroom, because the captain only attends when invited. In this case the First Lieutenant was a very high ranking

officer, and a charming man. His was a political appointment, and although he was probably never, ever, sick at sea, his

appointment did rather

smack of HMS Pinafore.

The popular game in the wardroom was Japanese Billiards. It comprised of a square wooden board, about a metre each way,

with a solid wooden "cushion" around it, and a pocket in each corner. A few centimetres inside the cushion was a square

marked with a line. On this surface there were a number of pieces, each consisting of a ring of wood with a hole in the middle

large enough to contain a fingertip. They were coloured red and green, with the exception of a white one. The game was played more

like pool than billiards, with each player flicking the white piece to make it knock their chosen colour pieces into a pocket.

The First Lieutenant was the wardroom champion, and he beat everybody else. For some reason he decided to take me under his wing,

and coached me in the technique of the game. By the time we came ashore after the sea trip I was able to beat everybody in

the wardroom except him. On one occasion he invited me to make the game "more interesting", which means putting a bet on it. I

knew that gambling was strictly forbidden on board, but he was in a position to make his own rules if he wanted to. So I asked

what he had in mind.

He suggested the Malvinas. If I won, Britain could keep them as the Falklands, otherwise they became Argentine property as the

Malvinas. So we played, and I lost. I also lost the best of three and the best of five. The following day we played again, and

with the same inevitable result.

Clearly this officer took the view that the Falklands/Malvinas situation was a political

distraction, not to be taken too seriously, and I am sure he would have been horrified to think we would ever be engaged in

a military conflict over it. And I certainly wouldn't like to think that

the eventual invasion of South Georgia and the islands themselves was simply the collection of a debt of honour. At least,

I have not heard anybody say so.

* * * * *

Some time after my visits I received a certificate from the senior sales manager for South America. In recognition of

having spent over 3 months in South America, it proclaimed my membership of the Ferranti South America Society, otherwise

known as the SAS. I also have the tie, which I wear on appropriate occasions.

During the subsequent Falklands conflict there were inevitably groups of people that took personal attitudes. There were political

pressure groups in Argentina, and there were ignorant members of the press in the UK. But at no time did I get the feeling

that the ordinary people in Argentina held the slightest animosity towards the British. When it had settled down I spoke

to people from our own South America sales team, and they confirmed that, other than suspending military sales for a while, it

was business as usual very shortly afterwards. The only problem was their continuing economic failure, and the way this

affected all trade with the country.

I was asked by several people whether the Veinticinco de Majo would be a significant asset during the conflict. I took the

view that Aircraft carriers

are essentially a means of getting an airstrip within a convenient range of the target zone. Other than that they are

a massive liability, needing a fleet of other vessels to defend them. In this case, I seriously doubted that

the steam catapult was capable of reliable operation, and that the Argentine navy had the resources to defend it at sea. In

the event I was correct, and the ship showed itself for only a very short while and only close to port.

* * * * *

I have always maintained a very strict rule. Whenever I am overseas I am in someone else's country, and their problems are

none of my business. Whatever I might feel is right or wrong for my own country, it is not my place to express a political

or religious opinion or to become involved in any campaign that might be going on in theirs. Of all the countries I visited

at work or on holiday, Argentina

was the most troubled. Of course I had my own opinions but I had learned that opinions formed in UK are based on

information available through the press or politicians. And this very frequently turn out to be ill-informed or deliberately misleading.

So I find it best to look, listen and learn, and above all to avoid any liklihood of embarrassment to my kind hosts, which

could do nothing but harm.

|